As much as this blog is about Maths, it’s also about rants. So here’s another one.

This one doesn’t come with an answer, just a question, and one I keep circling back to in lectures, problem sheets, and increasingly, in life.

What does it actually mean to prove something?

I’m sure this is a moment every budding mathematician hits eventually. You’re sat there in a lecture, staring at a proof that’s being written down far too confidently, wondering where the hell it came from. Not about how it works1, but why anyone thought to try that in the first place. I think that’s the weird thing about proofs, once you see them, they often look inevitable, obvious, even. And yet, before you see them, they feel like they’ve appeared out of thin air.

But when I’m sat in lectures, I don’t want to just see it, I don’t want to just check the algebra and nod along, I want to know what it means. And honestly? Most of the time, I don’t. Maybe that’s fine and maybe that’s the point. But I find it unsettling when you care about understanding, not just correctness.

At school, proofs felt procedural. You learn the structure and memorise the shape and one can get very good at that without ever feeling like you understand why those ideas are the right ideas. I mean, it works, I get marks, but something still feels hollow about it.

But since I got to university, that gap becomes more obvious. Proofs stop being just structures and start being… acts of creativity. Someone had to choose that approach. Someone had to guess the right definition to look at, the right thing to assume, the right object to construct.

And I can’t help but find myself wondering: how do people know where to start? How do you prove something that’s never been proven before? How do you even know what’s worth proving?

Another thing about proofs – once a statement is proven, it becomes solid. You’re not really allowed to question it anymore, at least not emotionally. The proof exists and there you go – case closed. But when you’re learning, proofs often don’t feel solid at all. They feel rather fragile, like if you stop paying attention for half a line, the whole thing dissolves.

This is where I find Maths slowly but surely starts bleeding into life. Humans are funny little creatures obsessed with proving things there too like proving we’re good enough. Proving we made the right decision, proving that how we feel is justified, proving that something will work out…

And just like in maths, we often rely on structures we’ve memorised and the narratives we’ve been taught. Say if X happened, then Y must follow and if I can justify it logically, then it must be okay.

But for some reason, life, inconveniently, doesn’t always respect clean assumptions. There are no axioms everyone agrees on and no universally accepted definitions. There is no guarantee that the thing you’re trying to prove is even true and yet, we keep trying.

While writing this point, I was reminded of one my early morning rowing outings in fog. Proper river fog, the kind where you can’t see the bank, or the next bend, and definitely can’t see where you’re going to end up. All you really have is the rhythm- catch, drive, finish, recovery. One stroke, followed by another, and again.

And it struck me how much that feels like trying to prove things. My brain hates the mental fog because I like to know why things work and what’s next. But the fog steals that. So of course everything feels harder and heavier because the usual tools don’t work well in low visibility.

But just like in rowing, you don’t get the full outline in advance, nor don’t get reassurance that you’re heading the “right” way. You just commit to the next stroke, trusting that if you keep moving and don’t panic, the river will still be there beneath you.

Lately, I’ve been trying to sit with something I’m not very good at accepting in maths or in life: I don’t know. I don’t know where that proof came from. I don’t know how I would have found it myself. I don’t know if my understanding is real or just borrowed. I don’t know if the questions I’m asking even have answers yet.

And maybe that’s okay. And not knowing doesn’t mean failure, it might just mean we’re standing at the edge of understanding, not the centre of it.

Maybe future me will read this and smile and think- ah, that’s obvious now. Maybe I’ll learn to see proofs less as magic tricks and more as conversations with structure. Maybe life will get clearer too. Maybe not.

But for now, as I’ve been reminding myself daily to cope with lectures and uncertainty and everything else life throws: I don’t know. It’s a mystery.2

And maybe that’s not something to fix just yet.

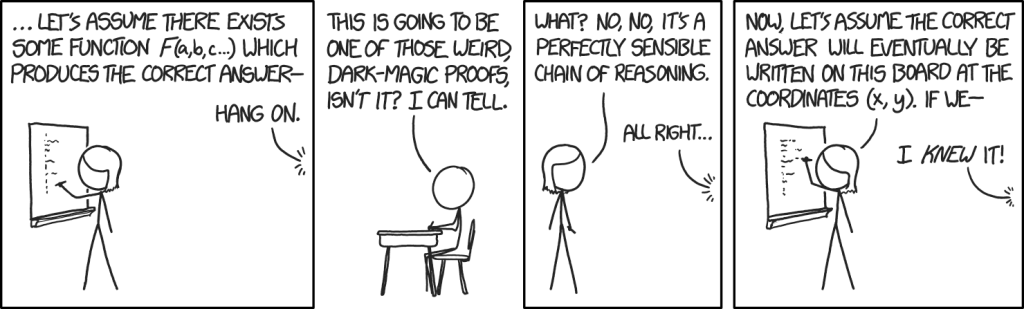

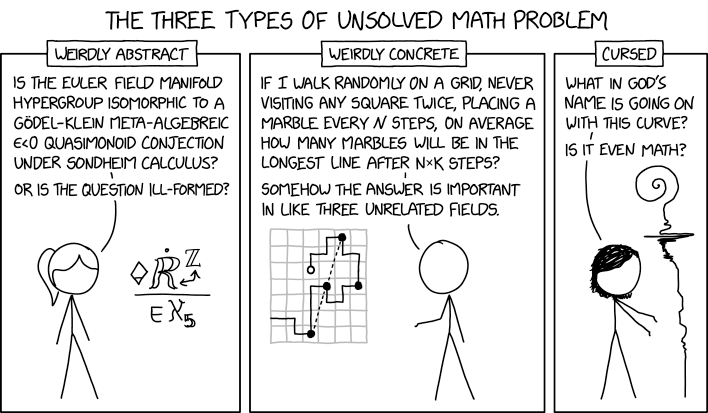

Sometimes after all that thinking about proofs, (un)certainty and life, I keep coming back to xkcd. So find attached a few of my favourite fun comics!

“The proof is left as an exercise to the reader”

LikeLiked by 1 person

Indeed. Full marks awarded for recognising this!

LikeLike