Having wrapped up a morning of introductory lectures, I was at the student pub playing a game of darts with some of my friends and trying to remember how on earth the scoring in darts actually worked. Why 501? Why does it feel so hard to finish even when you’re close? And who decided that missing a triple 20 should land you in the dreaded 1 or 5?

I’m no expert at darts, but being a maths student, I couldn’t not start thinking about the numbers behind the board. Darts, as it tuns out, is a lot more mathematical that people give it credit for.

Why 501?

Let’s get the obvious question out of the way. Why not 500? Or 100? Or something nice and round?

In the early 1900s, darts were played as 301, and they still are at times in pubs. It was useful for shorter and faster gabs for pubs where time and space were limited. As the sport professionalised, 501 became the tournament standard, it was long enough for skill to dominate, but not endless.

The choice 501 is odd1 for a few reasons. If you were to start on 500, it’s technically possible to hit two treble 20s and a double 20 to finish the game in a one throw. But 501 add that one awkward point. You can’t finish on a single bullseye or a high score, you need to land exactly 0, and your last dart must be a double.

The countdown system (i.e counting down from 501 instead of counting up) makes the game more strategic. You can’t overshoot, you must plan precisely to reach 0. It’s quite rare in sport where the goal isn’t to get as much as possible, but to hit exactly enough.

The Genius Behind the Dartboard

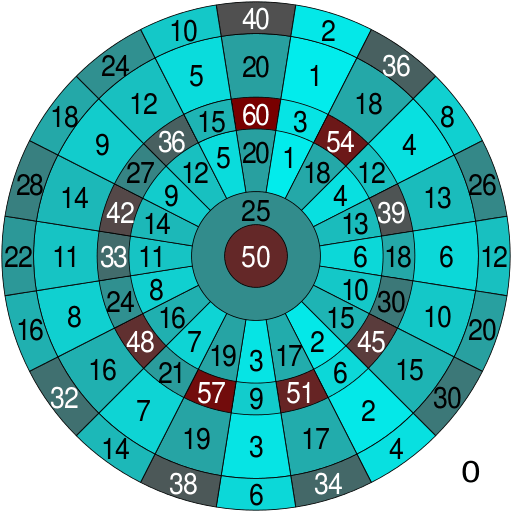

My first impression of the dartboard layout was absolute chaos, twenty numbers in no obvious order arranged around a circle with no good reason. Why aren’t they sequential? What’s the pattern?

The layout we know today wasn’t random, but a deliberate design by carpenter Brian Gamlin in 18962. Gamlin’s goal for design was simple: make accuracy matter. Early boards often placed numbers sequentially, so even if you missed, you’d still land close in value. That would tend to make the game dull and luckier rather than skillful. The arrangement then proposed was such that high value sectors were flanked by low value ones. If you miss a treble-20 by a few millimetres, and instead of 60 points you’d be starting at a miserable 1 or 5. It was brutal, but brilliant.

Mathematically, what Gamin created was a variance maximising sequence, he wanted to minimise the expected score of an inaccurate player. So if your throws are normally distributed around a target, an optimal numbering system is the one that keeps your average loss as high as possible when you miss.

Several mathematicians such as David Percy have experimented to find a theoretically perfect layout, and amazingly, the traditional board is almost optimal. Out of 20! (factorial) possible arrangements, Gamlin’s design ranks among the best3.

The layout also balances risk and reward beautifully. The outer ring doubles your score, the inner triples it. The bullseye is 50, its outer ring 25 which isn’t the highest value, but is centrally placed to reward precision. In this manner, each decision a player makes becomes a gamble, do you aim for the 20 bed4 with a huge payoff but a higher miss penalty, or play safe around 18 or 19 where neighbouring numbers are kinder? It’s the same tension as expected value problems in probability.

What’s even more interesting is the radial symmetry. The numbers alternate odd/even in a manner that no two adjacent large even numbers sit together. Every single throw is a little study in statistics.

A Point Well Thrown

What started as a break between lectures and problem sheets turned into one of those moments where I realised mathematics does really hide everywhere.

But the real reason I even picked up darts wasn’t even about the Maths. It was special thanks to my coursemate Jack Martin, who’s not only inspired and helped me in writing this post, but also been every so often reminding me to take breaks and step away from work. Ironically, playing darts has been one of my most productive distractions yet.

Honestly, that’s one of the things I love about maths, the way a simple pub game can contain layers of probability, geometry, optimisation and psychology. We often spend so much time looking for maths in textbooks, but sometimes it’s sitting on a bar wall. And sometimes, the best ideas land when you stop aiming so hard.

I know posts have been a bit less frequent lately, uni’s keeping me on my toes (and sometimes a few miles away from my keyboard). Thanks for sticking around, and for reading these little maths-meets-life rants. And I assure you, the ideas aren’t going away anytime soon, just taking a little longer to get onto a post!

- Pun intended ↩︎

- There is some debate to whom the credit goes to and whether Gamlin ever existed or not, but the design is commonly attributed to him. Some ideas for this post were thanks to darthub ↩︎

- That’s pretty good for a 19th century carpenter with no computer. ↩︎

- While researching to write this post, I came across quite a lot of darts terminology which was both exciting and at times intimidating, a comprehensive list to which can be found here. ↩︎