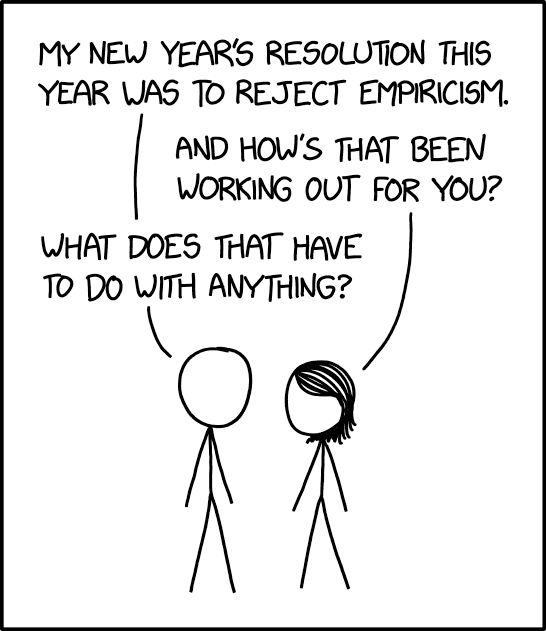

Every January, without fail, I write the date down wrong at least once. That’s expected. But what’s less expected is that my brain occasionally still wants December to be the tenth month. Which, objectively, it isn’t, but linguistically? It kind of is.

The names of the months don’t quite line up with their positions. September meaning seven, October eight, November nine, December ten, and once you notice it, you can’t unsee it. So, naturally, I wanted to know why does the year start in January, and why are the months misnumbered?

As it turns out, the answer is not mathematical elegance, but rather Roman bureaucracy.

When March Was the First Month

The earliest Roman calendar didn’t start in January at all. It started in March, which does make a lot of sense. March marks the beginning of spring, the start of the agricultural year, and historically, the season when military campaigns resumed, i.e. it was the month were things happened again.

That calendar had ten months. March being the first, followed by April, May, June and then months literally named by counting: fifth, sixth, seventh, eighth, ninth, etc. Winter didn’t really count as a structured period. There were days, sure, but not months in the way we think of them now. Timekeeping was tied to activity, not completeness. So if nothing productive was happening, it didn’t need a name. So December being the 10th month was perfectly consistent.

The Awkward Addition of January and February

Eventually, the Romans realised that having a chunk of the year floating around unaccounted for was… inconvenient. So two extra months were added to deal with winter, namely January and February.

January was named after Janus, the god of doors, transitions, and looking both forwards and backwards1. February was associated with purification rituals, endings, and cleaning things up before the cycle restarted. The counting-based month names stayed exactly where they were, and the calendar was just extended instead of being redesigned. Hence why December still carries a name meaning “ten”, even though it’s now the twelfth month2.

Even with January and February existing, the Roman year didn’t officially start in January because culturally and religiously, March still mattered more. However at some point, Rome decided that the year should begin when new political officials took office, and that date was January 1st, and it just made record keeping easier. And once that decision was made, January 1st became the official start3 of the year even if it felt a bit arbitrary.

11 minutes per year…

By the time we get to the 16th century, the Roman calendar had another problem and this time, a genuinely mathematical one.

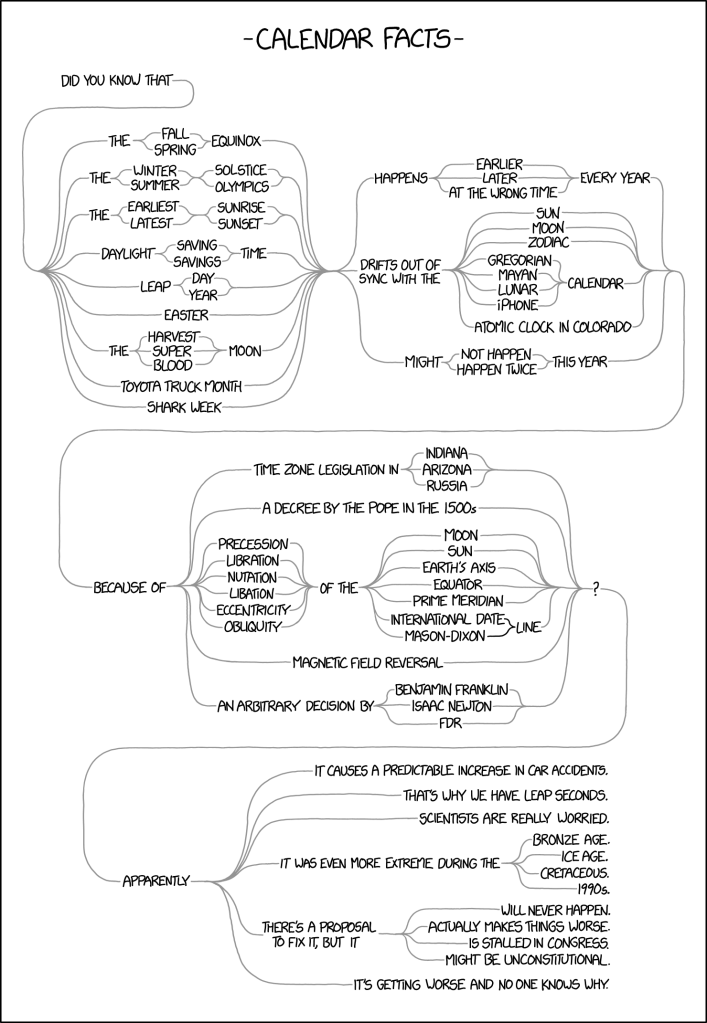

The Julian calendar assumed the year was exactly 365.25 days long. In reality, it’s slighter shorter, in fact, that tiny error of only about 11 minute4s per year doesn’t sound like much, but over centuries it adds up. Dates slowly drifted relative to the seasons. The spring equinox crept earlier and earlier in the calendar. This mattered because religious festivals were tied to specific astronomical events, so when Easter started slipping away from spring, it became clear that the calendar itself was misaligned with reality.

So in 1582, the calendar was adjusted under Pope Gregory XIII. The fix was pretty elegant, and it was to change the leap year rule. Years divisible by 100 would no longer be leap years, unless they were also divisible by 400.

Other Calendars, Other Priorities

What makes this more interesting is that our calendar is not the only reasonable way to measure a year.

Some calendars are lunar, i.e. prioritising months that align with the Moon. Others are lunisolar, constantly adjusting to keep festivals in the right seasons. Some calendars begin in spring, some in autumn, some on religiously significant dates. None of these are “wrong”, they’re just optimised for different things.

An off-by-two error, a correction term, and two thousand years of momentum later, we’re still here. Happy New Year.

This post was inspired by discussions on The Rest is Science podcast by Prof. Hannah Fry and science content creator Michael Stevens (Vsauce). Any good ideas mentioned here are theirs; any mistakes or confusions are entirely my own.

- Which is an almost suspiciously perfect metaphor for New Year reflection posts ↩︎

- From a mathematical point of view, this is exactly the kind of thing you’re told NOT to do. If your indexing is wrong, you fix the indexing. You don’t just shift the data and hope no one notices. ↩︎

- Which means that every time we celebrate New Year’s Day, we’re participating in a system designed two millennia ago to make Roman governance easier. ↩︎

- To be more accurate, it’s about 11 mins and 14 seconds (or 0.0078 days) ↩︎