Showing up to lectures early comes with perks beyond just getting good seats. Most mornings on my way in to one of the lecture halls, I walk past one particular poster (attached at the end of this post) which captures the beautiful shifting image of particle collision. Until recently, I’d never really thought about how or why that happened, or that process even had a name: lenticular printing. Inevitably, it had to become one of my posts, and true to form, here’s my attempt at explaining it without it (hopefully!) sounding like a boring Physics textbook.

A flicker through the History

The idea of making static images move is far older than modern posters. The roots go back in 1692, when artist Bois-Clair created tabula scatala (roughly translated to “staircase-shaped picture) paintings, two two images on alternate strips and viewed through angled mirrors. This principle was the basis of lenticular printing.

Then in 1908, French Nobel Prize winning physicist Gabriel Lippmann proposed “integral photography“, the use of a sheet of small lenses to record different perspectives of scene which would produce a depth or change effect when viewed through appropriate optics.

During World War II, techniques that underlie lenticular printing were explored for military training devices and optics. After the war1 with the rise of mass-manufacturing, lenticular sheets became cheaper and easier to produce. American inventor Victor Anderson of the company behind the trademark Vari-Vue popularised lenticular images during the 1950s/60s2.

Optics and Geometry

At its core, lenticular printing is part optics, part geometry, and a bit of ‘trickery’.

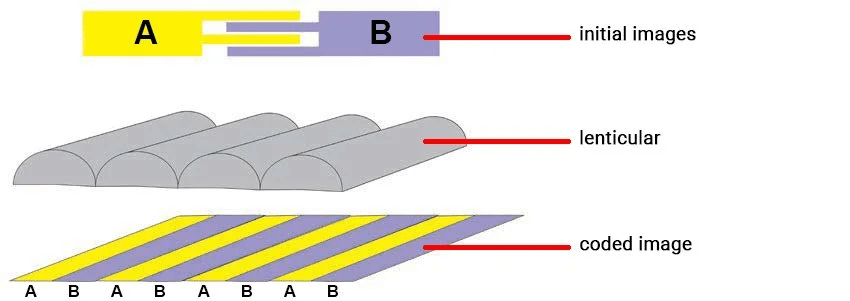

A lenticular print has two main layers:

- Top layer – the lenticular lens sheet

- This is a plastic sheet with lots of tiny cylindrical lenses (lenticules) running vertically.

- The smaller the lenticule, the more ‘scenes’ it can fit, with each one being visible over a smaller range of angels.

- Bottom layer – the interlaced image

- It’s made from several source images, each sliced into narrow vertical stripes and woven together.

Under the lens, each of the image strip lies at a slightly different lateral position under the lens.

The key idea here uses Snell’s Law, which will hopefully sound familiar if you’ve done Physics. As lends bends light according to Snell’s Law, and the lens is curved, light from different strips leaves the lens at different angles. From one viewing angle, the rays coming out that reach your eye mostly come from say strip A, and from another angle, they come from strip B, etc.

So when we move our position, we change the viewing angle, so our eyes are in line with a different strip’s light. Main thing to note is there the print hasn’t changed, but our line of sight through the lens has.

For 3D lenticulars, it’s the same principle, except instead of switching between different pictures, and the left and right eyes see slightly different perspectives of the same scene. Our brain amazingly fuses those two views into a single image with depth.

Like any good piece of engineering, it all depends on precision. If the interlaced print and the lenses are even slightly misaligned, our eyes will catch multiple strips at once, giving the double-vision shimmer that we can sometimes spot on postcards. It’s a magnificent illusion relying on geometry, printing, and perception.

Vs Holograms

At first glance, lenticular prints and holograms seem to do the same thing, they both make flat surface come alive with shifting images or depth. But their underlying workings rely on different physics.

Lenticular printing, as discussed above, is all about geometry and refraction. It uses an array of curved lenses to direct light from different printed images into different directions.

Holography on the other hand relies on wave interference. A hologram doesn’t store a flat picture, it stores the way the light was moving when it was bounced off the real object. Then when we shine light on it again, the pattern on the surface bends that light so it spreads out in exactly the same way as it did from the original object. Our eyes pick up those light rays and our brain thinks the object is still there even though it’s an interference pattern. So instead of seeing another image from a different image, we see the same light field recreated in 3D.

That’s why holograms have that ‘ghostly’ depth, they’re not showing us another printed image, but rather recreating the light field of the real thing. Lenticular prints redirect light; holograms rebuild it.

Applications (it’s more than just cool images)

What started as a clever optical trick has turned into a revolution in how we see printed images. Lenticular printing sneaks into our lives in more ways that we might expect. They can spotted everywhere from billboards posters and cereal boxes to autostereoscopic screens.

However, I find that of the most clever uses of lenticular printing isn’t in art or advertising, but in identity verification.

If you look closely at your driver’s license, or even some credit cards and passport pages, you might notice a small image or pattern shift as you tile it under the light. That’s often a micro-lenticular array, working on exactly the principle as the posters, but at a much smaller scale.

The brilliant property of aligning the lenticular array perfectly is what makes it impossible to photography or reprint an ID, we’d only capture one ‘frame’ of the lenticular image, exposing the fake instantly.

Just for fun – Anaglyph

If lenticular printing hides multiple images in space, anaglyphs hide them in colours. You might’ve not heard of the term anaglyph before, but you’ve probably seen retro 3D movie posters that look like a blurry mix of red and cyan until you put on paper glasses, with one lens tinted red and another tinted cyan.

Each lens in the glasses filters light by wavelength, so the red lens only legs red light through, while the cyan blocks red and only lets the blue-green light through. And our brain as usual, does the clever bit of combining those two slightly offset images into a single scene.

From lenticular lenses to holograms to anaglyph filters, there’s an entire field of optical cryptography out there. Whether it’s code or light, the idea is the same – hide complexity in plain sight, and reveal it only to those who know how to look.

- One might be tempted to say that field of lenticular printing essentially started as a curious project, got weaponsied, then became poster-board magic outside lecture halls. ↩︎

- This was also the era of 3D movies, apparently we really liked things jumping out at us ↩︎

- If you haven’t already, let this be your sign to re(watch) Star Wars ↩︎

Pingback: Le guide lenticulaire ultime - Impression lenticulaire de vos photos