There’s something really nice when you look at the curve in all these photos. You can see it in the power lines, the arc of a chain, or if you’ve ever looked closely enough, a spider web. Part of the inspiration for this post goes to my chaotic but lovely FM Mechs class where we would joke about this oddly specific curve. But the more I noticed them, the more I get it, they’re everywhere, and they’re kind of beautiful, and this post is all about that curve: the catenary.

So… what even is a catenary?

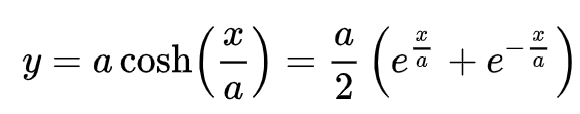

Catenary is just the name for the curve a chain or a cable makes when it hangs under its own weight between two points. Mathematically speaking, the equation of a catenary is in the form of:

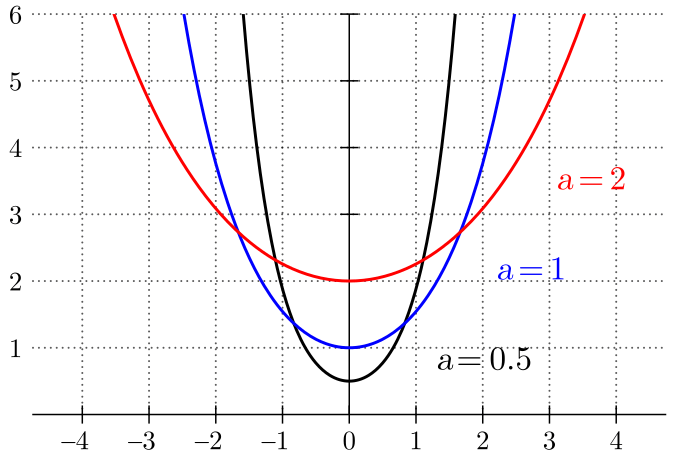

where cosh is the hyperbolic cosine function, and where a is the distance of the lowest point above the x axis. The equation above is essentially the answer to the question: What curve minimises gravitational potential energy for a hanging chain?

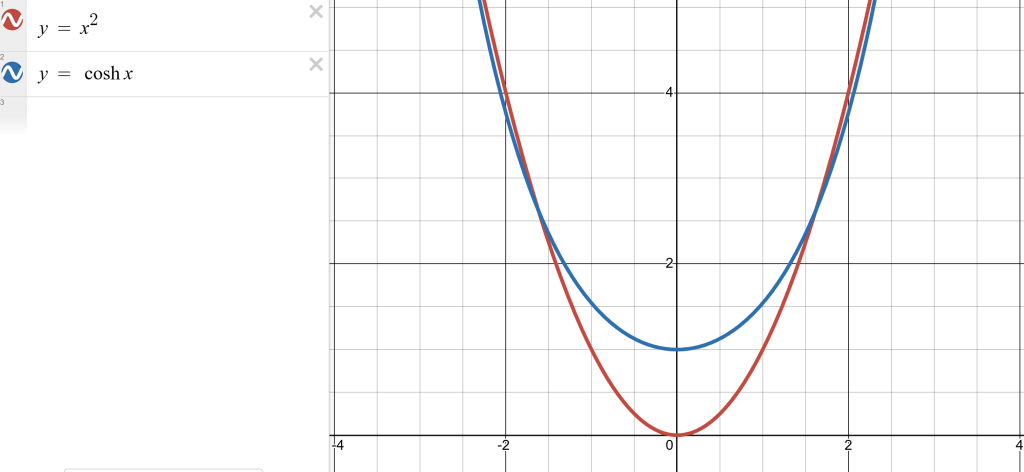

This curve may look similar to a parabola, but it’s not. A parabola is the name of the curve we get when we throw something in the air. It’s linked to projectile motion and the constant acceleration of gravity. The red graph below shows a parabola, whereas the blue graph shows a catenary.

To put it simple: a curve formed when something is thrown is a parabola, if a curve is a formed by something hanging, it’s a catenary.

And as it turns out, the catenary is exactly the shape that minimises potential energy1. You don’t need to grind through all the calculus to appreciate what’s happening. The key takeaway is that a hanging chain finds the shape that balances every little force perfectly, and the maths just tells us that the shape is in the family of hyperbolic cosines.

Catenaries in the wild

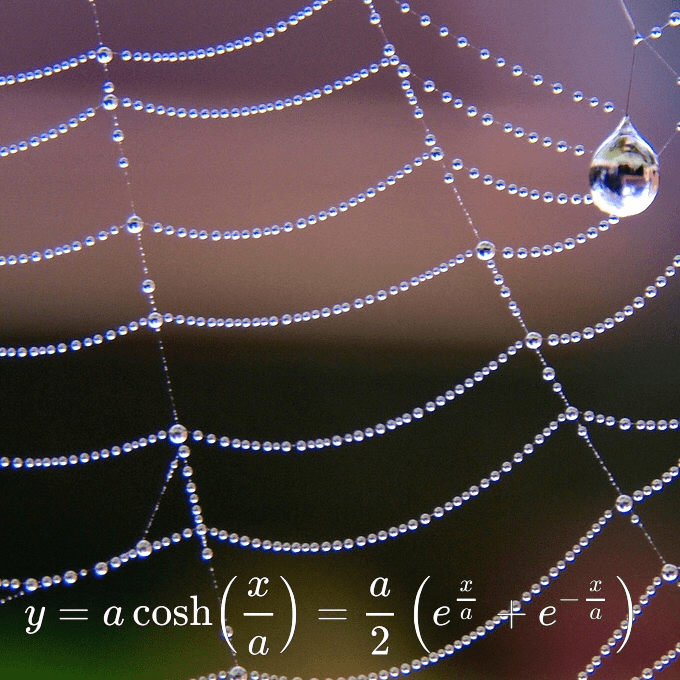

Once you start spotting catenaries, you can’t stop. Chains, cables, spiders webs, bridges, the same concept keeps showing up, and the reason is pure (or applied) maths.

Spiders don’t sit there solving differential equations, but somehow, their webs end up following the same rules. When a spider spins a thread between two twigs, gravity instantly tugs it into a catenary. The flexible silk can fall into the shape that balances all the forces perfectly. The next time you’re out, try and look closely at a web in the morning dew for the curve. Each tiny droplet adds weight which extends the strand.

This is the same mathematics that the Spanish architect Antoni Gaudí used in his designs for arches. He knew that if you flip a hanging chain upside down, you get (in theory) the perfect arch. In that orientation, the weight of the structure flows straight down the curve, compressing the material instead of bending it. Gaudí built models with hanging chains and weights. He’s let them droop into natural catenaries, then place a mirror underneath. The reflection gave him the arch shapes he wanted for buildings like the Sagrada Família in Barcelona.

Engineers use the same idea on bigger scale for suspension bridges.

Why this matters

When doing Further Maths, I never really realised how much of that content would be actually applied. Like I remember learning hyperbolics and the cosh curve, but not as a useful catenary with all of its amazing applications. In fact, it wasn’t until one day I really noticed a spider web, in a more mindful way, that I learned about catenaries and decided to write a post about it.

It’s amazing how the same up shows up in both nature’s smallest webs and the largest bridges built. From spiders to suspension cables, everyone ends up trusting the catenary.

- I was originally going to write an optional extra section on how we know the catenary is not a parabola and more about the derivation of the equation using differential equations, but that has been postponed until sometime later… If you’d like to read more about it however, check out this link here. ↩︎