Ever wondered why you sometimes get perfect signal in some random field in Wales but can’t even load a message while inside a lift? Or how you’re able to make an emergency call even when your phone says No Service? Or why your phone switches from 4G to 3G (or refuses to load anything at all) just when you need it most? And why does airplane mode exist?

We rely on mobile networks every day to talk, text, scroll, some might even say- survive. But most of us don’t think twice about what’s actually happening when we hit send or open an app.

Having spent the better half of my past few days in the countryside, I wanted to write a post that explores the clever systems that power the phone signal, and also investigate why phones always lose connection in the worst possible moment…

Waves, Frequencies, and Fourier transforms

Every time you send a message, stream a video, or open an app, your phone sends information through the air using radio waves1.

Each mobile generation (3G, 4G, 5G) is defined in part by the frequency bands it uses. These bands are measured in megahertz (MHz) or gigahertz (GHz), and the higher the frequency, the more data you can transmit2

You might remember from Physics that the relationship between frequency and wavelength is given by:

λ = c/f

Where:

- λ is the wavelength (in metres)

- c is the speed of light (3 x 108 ms-1)

- f is the frequency (in Hz)

For example, 5G networks operating at 26 GHz have wavelengths shorter than a centimetre, which is why 5G struggles to pass through buildings, while 3G (around 900 MHz) can still reach your room.

However, mobile communication isn’t just about single frequencies. A sound wave can be described by how it changes over time, but what if you wanted to know what frequencies made up that sound? Signals are a mixtures of different waves, and that’s where Fourier transforms3 come in.

In short, a Fourier transform is a function that takes in a signal and represent it as a sum of sine and cosine waves. This means your phone can and the network can decode what’s being transmitted, even if the signal is distorted, noisy, or partially lost. In fact, almost everything digital, from Spotify compression to MRI scans to reading a wireless, relies on Fourier analysis to break down, understand and reconstruct information.

Why you have signal in some places but not others

One might think that mobile signal would just depend on how close you are to a tower. But it’s not quite that simple.

Some of the best signal you might get could be in a random valley Wales, while a metal lift in the middle of a city centre gives you nothing. This is because signal doesn’t just depend on distance, but geometry, interference and infrastructure all play a role in how radio waves reach your phone (or don’t).

Mobile networks are called cellular networks for a reason. Areas around the world are divided into cells, each served by a different tower. If you were to draw these on a map, they would look hexagonal, and this ideal layout of cell coverage is modelled using a Voronoi diagram4. This allows us to split space so that each point belongs to the region of the nearest tower. In practice, terrain complicates things and distort signal. So in the real world, cell boundaries aren’t exactly neat hexagons. This is also why cities with lots of towers can cause people to lose signal, as more people will be using the same cell, leading to network congestion.

Speaking of lifts and elevators- the metal in the walls reflects or absorbs the radio waves, stopping them from reaching your phone. They’re basically a Faraday cage, and the same thing happens in underground car parks, tunnels, or certain trains.

So is a wide-open field better for signal than a city? Not really. Sometimes fields do give good signal, but rural areas have fewer towers, which means larger cells, and therefore weaker signal. The strength of a radio signal also follows the inverse square law, so if you move twice as far from the towers, the signal spreads over four times the area, with your phone only receiving a quarter as much.

What actually happens when you have ‘no bars’

We’ve all been there. You open your phone to check for messages and either see the sign for ‘No Service’ or one sad little bar at the corner. But what does this actually mean?

Firstly, signal bars are not an accurate measure of internet speed, but a rough visual of signal strength, i.e. how well your phone can hear the tower and decode the signal. The bars don’t tell you about how busy that tower might be, or how fast the data can actually travel through the system. So having four bars doesn’t guarantee fast data, you can have high signal and terrible internet, or low signal and a surprisingly stable connection.

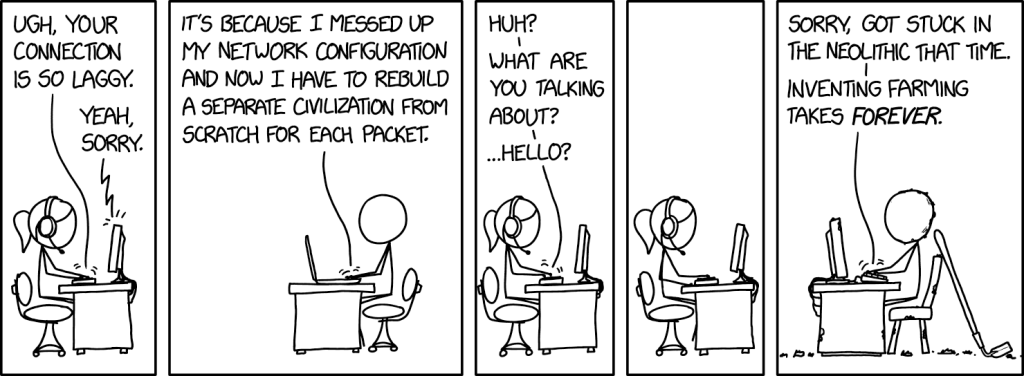

Whenever you send data across the network, it gets broken into small chunks called packets that travel individually through the network (packet switching) and get reassembled at the receiving end. But when the signal is poor, the packets can get delayed, arrive out of order, or get lost entirely.

When a packet is lost or the data is incomplete or corrupted, your phone can still recover it thanks to error correction. And if that fails, the data will have to be sent again which takes time. This is also why your phone will sometimes switch to lower frequencies in poor signal areas, because they travel further. So the next time you drop from 4G to 3G, it’s just your phone trying to salvage connection and deal with detecting errors.

How emergency calls work without service

‘No Service’ doesn’t mean no signal at all, but rather ‘You have no signal that you’ve paid your network provider for’

Emergency calls are governed by standardised protocols5 which mean that even if you have no SIM card6, or you’re out of credit, or your provider has no coverage in an area, your phone is still legally required to attempt emergency connection through any available network.

If no towers at all are reachable, then you’ll get ‘No Signal’, and emergency calling won’t work either.

Network towers

Whenever your phone switches between 3G, 4G, 5G, it’s connecting to one of the thousands of physical towers. But who owns them? And how do operators cooperate?

In the UK, most large telecom towers are operated by BT7 or were once run by Arqiva, with many sites now managed by Cellnex. Globally, the top 10 tower companies (American Tower, Cellnax, Crown Castle) control over half of the world’s cellular sites

Building a tower is expensive (and often unnecessary). So operators cooperate through infrastructure sharing, which uses graph theory and optimsation techniques8 to place towers in a way that minimises gaps in coverage, maximises efficiency, and meets the capacity demands. With the growing use of 5G, small cells (mini towers) are added to fill capacity gaps in dense areas.

5G and MIMO

Why does 5G feel so much faster than 4G? How is it different and how does it work?9 One of the big workings behind the speed of 5G is MIMO.

MIMO stands for multiple input, multiple out. It essentially allows us to dramatically boost data capacity without needing more frequency bandwidth by sending multiple data streams simultaneously via multiple antennas.

Airplane mode

You’ve just boarded a flight, seatbelts on, tray tables up, and then the routine annoucnement of putting on phones in airplane mode. Ever wondered why? I certainly did, but never really understood why until recently.

When you switch on airplane mode, your phone basically disables all radio transmitters. (Okay, but still why?)

The main concern is radio interference, specifically, interference with aircraft communications and navigation systems. Mobile signals, especially when searching for towers at altitude emit high-frequency radiation which can potentially interfere with the cockpit instruments. Moreover, phones on the ground connect to the nearest tower, but at high altitude, your phone might detect many towers below and switch between them constantly, which would just cause network strain.

But what about Wi-Fi on planes? Because plane Wi-Fi is connected to a satellite antenna or air to ground network. It’s a controlled radio system, unlike a free roaming phone trying to make a call.

Final thoughts

Next time you send a message or call a friend, remember that you’re not just holding a phone, you’re holding the endpoint of a vast, invisible, mathematically optimised network. We owe our ability to communicate, to a world built on equations. 10

So when your phone clings to one bar in a crowded city, or your miraculously get signal on the Pontcysyllte Aqueduct, I hope you’ll think about all the remarkable maths including Fourier transforms that goes in the background. Until next time, stay curious, stay connected 🙂

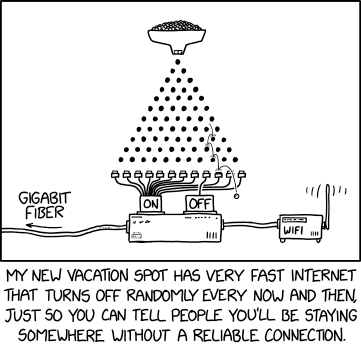

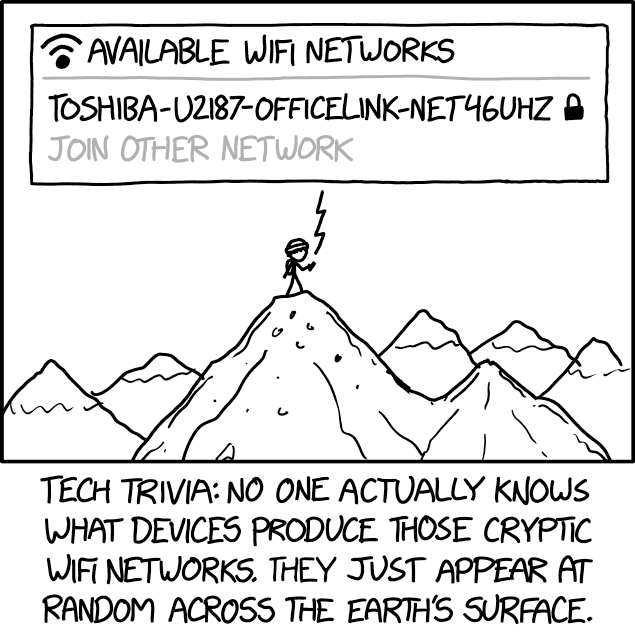

P.S – xkcd11 screenshots because why not..

- Radio waves are part of the Electromagnetic (EM) spectrum. There are low energy and long wavelength, so perfect for travelling long distances ↩︎

- This, of course, comes at the cost of range and wall penetration ↩︎

- In all honesty, I’m yet to be formally and mathematically learn this topic, but from what I’ve read, it’s one of the most beautiful bits of applied maths ↩︎

- A Voronoi cell is the set of all points that are closest to a particular towers compared to any other. You can read more about this here ↩︎

- Protocol is set of rules that determines communication between devices on a network ↩︎

- Yes you can make emergency calls without a SIM card. Your phone still has a radio and the ability to scan for nearby towers. It just doesn’t have credentials, but in an emergency, these don’t matter. ↩︎

- You can find more about this here ↩︎

- If you’ve read/studied network algorithms, this would be an area they will be used. ↩︎

- There’s been a fair bit of community chatter about whether 5G causes brain damage and other health issues. I’m not going to write much on this, but from the scientific community, there is on strong evidence to back up such claims. ↩︎

- I’d like to imagine myself saying this in Carl Sagan’s voice… ↩︎

- If you’ve never heard of xkcd (firstly get a life, how have you made this far without knowing of xkcd’s exsitence?! /jk), do check it out here! ↩︎